Pack Membership and Roles in Race Competitions

December 26th, 2020

Introduction🔗

Integrating an understanding of pack patterns into our analysis can unveils different mechanisms affecting how races unfold. Packs tend to effect athlete behavior in a simple way: members of a pack tend to stay members of the pack. This effect helps members of pace groups to keep pace and achieve their goal finish time. This also means that competitors can use packs of a faster rival team members to their advantage by joining it. However, this effect also means that a pack member may stay with the pack, even when the pack’s pace is not in their self-interest (i.e. winning a race, getting a personal best, etc.). A pack leader could intentionally increase/decrease the pace to give themselves a competitive advantage later in the race. This is often seen in championship races where a fast field runs the majority of the race at a much slower pace, and then kicks at the very end. This gives a competitive advantage to competitors who have the strongest kick at the end of the race.

What is a pack?🔗

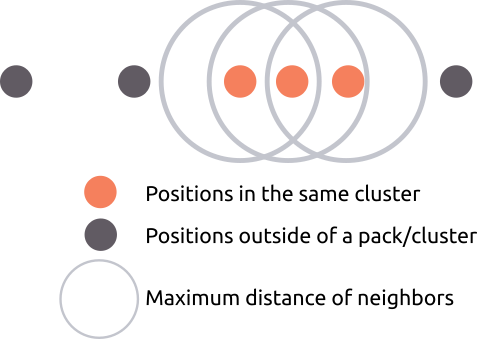

Before we go further, we need to differentiate between a cluster and a pack of competitors. A cluster of competitors is a group that has a minimum number of competitors within a given distance of each other. In other words, they are all close to each other. A pack is a group that has a minimum number of competitors within a given distance of each other, and is traveling at the same speed in the same direction. In other words, they are all close to each other, and are all close to each other for a length of time. Since a pack is simply a cluster with an added speed similarity constraint, we can know that if a group qualifies as a pack, then it also qualifies as a cluster. We can also infer that a cluster can contain 0 or more packs, as the members of the cluster may contain multiple sets of people travelling at different speeds together. As an example, when one pack is passing another, for a short time they both make up a single cluster since they both occupy the same space, but they are still 2 separate packs due to the differences in speed.

In a race, packs can be calculated based on splits that are recorded at specific distances throughout the race for all competitors. These splits give the analyst a discrete number of snapshots of when each competitor passed each specific distance. For example, in a 1 mile track & field race, splits could be taken every 200 meters, which would give the analyst a view of the race at 200m, 400m, 600m 800m, 1000m, 1200m, 1400m, 1600m, and 1 miles. Analysts tend to want many evenly distributed splits throughout a race, as they provide more unbiased views into the progression of a race both in terms of packs/clusters, and of each individual competitor.

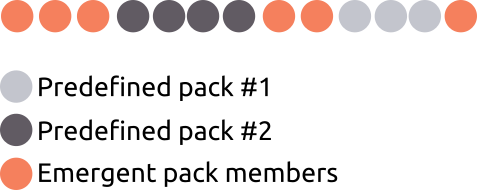

Packs can be organized into 2 broad categories (with subcategories):

- Predefined

-

A pack whose members are defined prior to the competition.

- Public

- A pack that is defined publicly prior to the start of the competition with a specific purpose and behavior. Anyone can freely join/leave this type of pack. Ex. pace group, military charity group, lead pack in a rabbited race, etc.

- Private

- A pack that is privately defined with specific purpose, behavior, and membership. Ex. A group of people pacing their mutual friend, a coach telling specific team members to stay together in the race, a pack of family members, Eliud Kipchoge’s pace groups throughout the exhibition to break the 2 hour marathon, etc.

- Emergent

- A pack that is not defined or planned, but dynamically occurs based on the individual behaviors of the participants in the competition. Most packs are of this type. Ex. A group of competitors who happen to be running same pace and happen to be near to each other, etc.

All packs are fundamentally made up of competitors, but emergent packs can also contain predefined packs. For example, if one or more predefined packs joined together for a given period of time, they would be forming an emergent pack. Or, if competitors randomly joined a predefined pack , they would form an emergent pack. As predefined packs have predefined memberships, those predefined packs can still be identified within emergent packs (assuming the predefined members are still in close proximity of each other in the emergent pack.) This concept allows us to create a hierarchical visualization of pack membership & behaviors.

Packs have different properties which define how the packs look and how they might behave:

- Density

- How many competitors are within a given amount of space. This metric tells us how tightly bound a pack is.

- Spread

- How much distance the pack is spread over, or time it takes for the group to pass a given point.

- Composition

- Proportional commonalities of pack members, such as age, gender, affiliate, sponsor, goals, etc. Lower proportions indicate that the members of a pack tend to be different from one another, and that the pack is most likely emergent.

- Retention/Cohesion

- Describes the tendency of a given competitor to stay within a pack once joined, or the tendency of competitors to stay within a given pack. For example, in a predefined pack with a very strong retention rate, the pack will likely only go as fast as the slowest member can sustain to ensure the pack stays together.

These properties can be used to describe packs, distinguish between packs, and to identify roles of pack members. For example, a predefined pack of team members may have a very high retention rate, in that no members leave the pack the entire race.

Pack Membership/Roles🔗

Packs and individuals can have different roles throughout a competition, based on position, objective, etc. These roles can be static, or constant throughout a race, as in the case of a pacer, Or these roles can be dynamic, where roles can change depending on position of the pack/individual. Dynamic roles exist in almost all competitions, while static roles tend to only exist in predefined packs. Here are some common dynamic roles of individuals within packs:

- Leader

- The front-runner of a pack, a dynamic role typically a competitive athlete. In emergent packs, this member typically sets the pace for the pack

- Core

- A dynamic role of the members in the middle of the pack, typically where the density of people is the highest. This can also be defined as members with a minimum number of competitors within a given distance of them.

- Rear

- The dynamic role of the last person in the dense part of the pack

- Trailer

- A dynamic role of a person who is just outside of the dense part of the pack. Typically members in this role will be leaving the pack shortly thereafter, or the pack will leave

- Rabbit/Packer

- A static role indicating that the individual sets the pace of the pack. This role can also be viewed as a leader of the pack. A pack will not typically yield leadership of the pack to another member, unless the specified pace is not being set

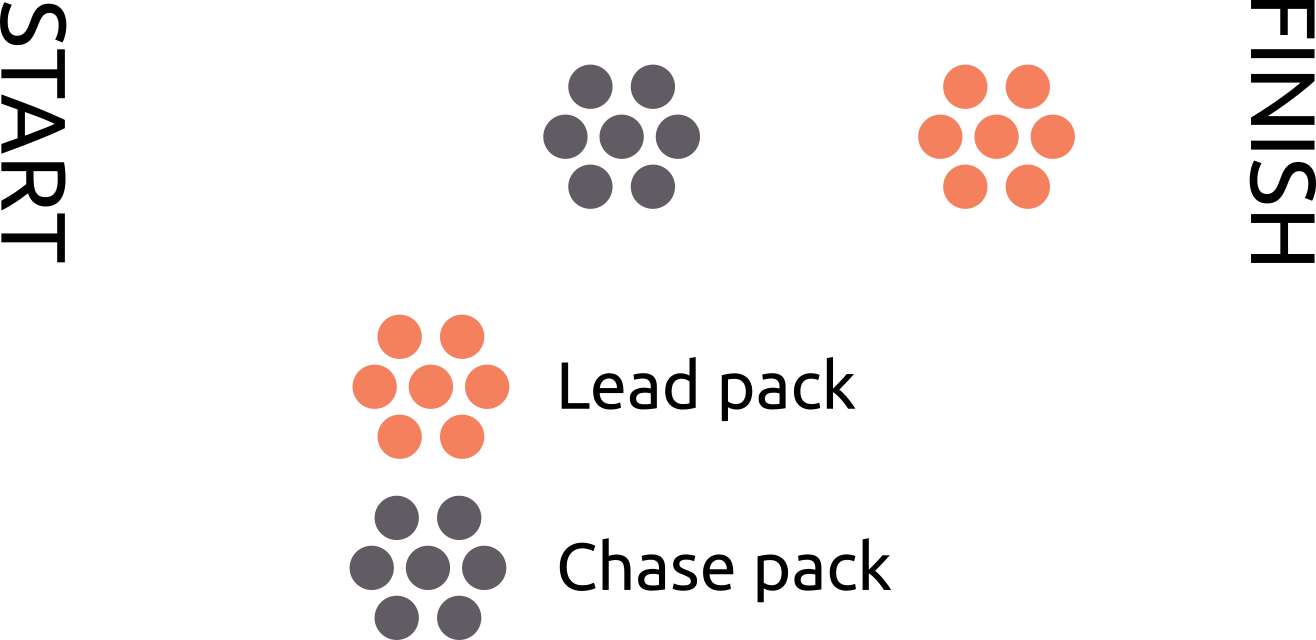

Packs can also have roles within a competition:

- Lead

- A dynamic pack. The first pack in a race, typically full of competitive athletes

- Chase

- A dynamic pack. The second pack in a race, usually looking to join, pass, or stay within a given distance of the lead pack

- Corale

- A static pack with the purpose of keeping a specified pace for the entire race

- Absorber

- A dynamic pack that absorbs individuals/smaller packs throughout the duration of a race

- Shedding

- A dynamic pack that loses members throughout the duration of a race

The roles above can all be used to describe how a given individual/pack behave throughout a competition. For example, if an individual was in a Leader role throughout the competition, but finished in a a Trailer role, we can compare their paces with the average pace of the pack to determine if they slowed down, or if that pack sped up towards the end of the race. If a pack tends to be in a Shedding role where the departing packs tend to be moving ahead of the pack, we can guess that the pack’s pace was being limited beyond the tolerance threshold of the departing packs. While these are simplified examples, other factors could be considered to get a more comprehensive view of the behavior of packs.

Many packs may have multiple dynamic roles throughout the course of a given race. For example, a pack may be the lead pack for the first 25km of a marathon, and then become the chase pack for the last 17km of a race. The splits of a given race could be broken down into sections to determine the role of each pack/cluster/competitor during that section of the race. In a real-life application, this would also allow for more detailed views of a particular section of the race which happens to have a higher density of splits than other parts of the course.

Automation/Storage of Pack Membership🔗

Any person watching a race can easily determine where each pack start/ends. To integrate pack behavior into how we assess past, present, and future races, we must be able to computationally determine pack membership/roles to provide the information for past races, and for live broadcasts. While intra-race race analysis would be useful for live broadcasts, inter-race analysis would be needed for coaches/athletes to draw conclusions on race strategies.

The following steps are involved in analyzing intra-race packs:

- Identify clusters

- Identify clusters at each split by grouping competitors that meet the required minimum density requirements.

- Identify packs from clusters. This is done by finding groups within each cluster that still meet the minimum criteria for being a cluster over sequential splits. During this initial stage, the position of the pack could be determined by averaging the times of the members of each pack to get an average time of the pack.

-

Identify pack/cluster identity over time and membership changes For example, the following visualization illustrates how pack/cluster membership changed through the men’s marathon at the XXXI Olympic Games:

- Assign roles to packs and pack/cluster members

- Track changes in roles over time in competitors and packs/clusters. Does the competitor tend to move from the core of the pack/cluster towards the rear? Does the lead pack/cluster end to exchange competitors with the chase pack?

- Pattern recognition on pack co-membership between athletes throughout a race. Does the competitor tend to be the same clusters/packs as another competitor(s)?

- Pattern recognition on pack membership changes of athletes throughout a race. Does the competitor tend to stay in the same pack for the duration of the race? Does the the competitor tend to change membership to faster/slower packs?

- Pattern recognition on role changes of athletes throughout a race. Does the competitor tend to be the leader of whatever pack/cluster they are in?

How these calculations are made/optimized can vary by sport, the number of dimensions that need to considered, etc. In sports such as track & field, swimming and cycling only one dimension (distance in competition) is considered, which allows us to write a clustering algorithm that can run in linear time based on the number of participants.

Pack memberships and roles can all be calculated using the splits and finish times of the participants of a race. As more splits are provided, more detailed pack memberships and role information can be provided on a race. Some factors such as these can also contribute to a longer computation time of these pack memberships and roles:

- Number of participants. As the number of participants in a competition increase, the number/size of potential packs increases, thus extending computation time linearly with the number of total participants.

- Number of splits. As more splits are recorded for participants, the computer will need to compute the changes between each set of splits, which will also linearly extend computation times.

By finding the clusters at each split in parallel, and finding the changes in pack memberships in parallel we can minimize the execution time based on number of splits, however the linear growth of execution time based on the number of participants remains. As there is a limit on the number of participants a competition can accommodate, I believe that the growth of execution will not be an issue.

Inter-race pack analysis directly depends on the intra-race pack analyses. The following calculations are involved in inter-race pack processing, but can be processed concurrently:

-

Pattern Recognition

- Pattern recognition of roles across races. Does the competitor tend to have the same role (or subset of roles) in each race? Does the the competitor tend to have the same roles throughout different sections of the race?

- Pattern recognition of changes in membership across packs across races. Does the competitor tend to move from/towards particular packs? Does the competitor tend join/leave packs with a given competitor?

-

Pattern recognition on pack co-membership between athletes across races. Does the competitor tend to be members of the same clusters/packs of other particular competitors?

- Anomaly Detection - Is the competitor/cluster/pack behaving in an unexpected way?

As more athlete participate, and athletes participate in more races pattern recognition computation time will increase non-linearly, and patterns for more time intervals will need to be calculated. Because of that non-linearly growth in computation time, pattern recognition algorithm implementations need to be optimized, and pattern recognition tasks need to be executed in parallel to reduce the total time to delivering the patterns to the athletics community.

To be viable for widespread use, cluster/pack calculations and pattern recognition would need to be fast enough to be calculated and rendered during live media broadcasts such as major marathons, Diamond League events, and Olympic Games. This makes the actual implementation of the process to be of the utmost importance. So let’s move on to actually implementing code that would perform this task. For smaller races, existing general implementations of DBSCAN can be used to identify clusters. Here is an example of how to find the clusters for splits at a specific distance:

from sklearn.cluster import DBSCAN

entity_ids = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, ...]

entity_splits = [[932.0], [938.0], [938.0], [940.0], [933.0], [950.0], [1009.0], [933.0], [940.0], [940.0], [969.0], ...]

max_epsilon = 2.0

min_pack_size = 3

clf = DBSCAN(eps=max_epsilon, min_samples=min_pack_size)

clf.fit(entity_splits)

clusters = clf.labels_

print(clusters) # array([ 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, -1, -1, 0, 1, 1, -1])

for entity_id, performance, cluster in zip(entity_ids, entity_splits, clusters):

is_in_pack = cluster > -1

print(entity_id, performance, is_in_pack, cluster)More efficient implementations can be developed that account for how the data is received/structured, or for online computation.

The following code is such a clustering algorithm that does run in linear time and online computation of clusters. Online computation means that the algorithm support clustering competitors as splits become known.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

class DBPack(object):

"""

A special case of DBSCAN, where each point has a single dimension, are in ascending order

and one can guarantee that any further points will be >= the last point that has been clustered.

Can be applied to recording clustering a time series of events based on their timestamps

Can also be applied to online clustering in linear time using __call__

"""

OUTLIER = -1

__slots__ = ('eps', 'min_points')

def __init__(self, eps, min_points):

self.eps = eps

self.min_points = min_points

def __call__(self, X, cluster_assignments):

existing_sample_count = len(cluster_assignments)

total_sample_count = len(X)

max_index = existing_sample_count - 1

cluster = 0

for i in range(existing_sample_count, -1, -1):

if cluster_assignments[i] != self.OUTLIER:

cluster = cluster_assignments[i]

break

while max_index < total_sample_count:

neighbors, max_index = self._neighbors(max_index, X)

if len(neighbors) >= min_points:

for index in neighbors:

clusters[index] = cluster

cluster += 1

max_index += 1

return clusters

def fit_predict(self, X, y=None):

cluster = 0

max_index = 0

sample_count = len(X)

clusters = [self.OUTLIER for _ in range(sample_count)]

while max_index < sample_count:

neighbors, max_index = self._neighbors(max_index, X)

if len(neighbors) >= min_points:

for index in neighbors:

clusters[index] = cluster

cluster += 1

max_index += 1

return clusters

def _neighbors(self, max_index, X):

output = set([max_index])

sample_count = len(X)

distance = 0.0

current_point = X[max_index]

while distance <= self.eps and max_index < sample_count - 1:

neighbor_index = max_index + 1

neighbor = X[neighbor_index]

distance = abs(neighbor - current_point)

if distance > self.eps:

break

output.add(neighbor_index)

current_point = neighbor

max_index = neighbor_index

return output, max_index

if __name__ == '__main__':

raw_data = [7344.0, 7380.0, 7392.0, 7451.0, 7466.0, 7478.0, 7493.0, 7499.0, 7499.0, 7510.0, 7543.0, 7563.0, 7569.0, 7569.0, 7580.0, 7591.0, 7609.0, 7620.0, 7623.0, 7631.0, 7638.0, 7645.0, 7663.0, 7665.0, 7667.0, 7686.0, 7691.0, 7701.0, 7701.0, 7702.0, 7735.0, 7750.0, 7755.0, 7760.0, 7777.0, 7790.0, 7796.0, 7797.0, 7805.0, 7809.0, 7811.0, 7814.0, 7819.0, 7820.0, 7821.0, 7828.0, 7833.0, 7849.0, 7853.0, 7853.0, 7862.0, 7874.0, 7877.0, 7878.0, 7880.0, 7886.0, 7891.0, 7894.0, 7896.0, 7897.0, 7899.0, 7900.0, 7904.0, 7929.0, 7945.0, 7953.0, 7958.0, 7961.0, 7963.0, 7964.0, 7970.0, 7978.0, 7998.0, 7998.0, 7999.0, 8021.0, 8021.0, 8025.0, 8033.0, 8056.0, 8062.0, 8063.0, 8070.0, 8074.0, 8110.0, 8113.0, 8118.0, 8119.0, 8125.0, 8137.0, 8151.0, 8151.0, 8152.0, 8169.0, 8192.0, 8214.0, 8237.0, 8249.0, 8268.0, 8275.0, 8278.0, 8284.0, 8285.0, 8303.0, 8304.0, 8308.0, 8322.0, 8345.0, 8352.0, 8361.0, 8365.0, 8370.0, 8380.0, 8383.0, 8394.0, 8416.0, 8445.0, 8454.0, 8457.0, 8490.0, 8506.0, 8512.0, 8520.0, 8533.0, 8540.0, 8545.0, 8563.0, 8569.0, 8590.0, 8611.0, 8810.0, 8834.0, 8850.0, 8858.0, 8882.0, 8895.0, 8896.0, 8904.0, 9148.0, 9347.0, 9419.0]

eps = 2

min_points = 3

clf = DBPack(eps, min_points)

This logic can also be expanded to identify clusters/packs based on known factors, such as pacers, rabbits, competitor affiliations, or social networks to define more specific clusters within the race. Some aspects of the logic in latter steps would potentially needed to be updated to allow for competitors to potentially be members of multiple clusters at each split.

After identifying the clusters at each split distance throughout the race, we need to find which clusters persist over sequential splits. There are many valid approaches to this, all of which are based on density-based clustering. We can identify clusters using the convoy approach from Discovery of Convoys in Trajectory Databases or moving clusters, and/or using the moving cluster approach from On Discovering Moving Clusters in Spatio-temporal Data.

Today, how to do this using the moving cluster approach. The moving cluster approach works step-wise through the splits, if two clusters’ similarity exceeds a given threshold, then the two clusters in each split are considered the same group. In this case, we will measure similarity using the Jaccard coefficient, specifically as the proportion of competitors that are members of both clusters. The code below show exactly how this is computed

def jaccard(cluster1, cluster2):

"""

Computes the Jaccard coefficient for items between two sets, based on the numbers that are within both sets

Args:

cluster1(set): The bib numbers of competitors in a given cluster

cluster2 (set): The bib numbers of competitors in another given cluster

Returns:

float: A 0 >= number <= 1 representing the similarity between the clusters

"""

intersection = cluster1 & cluster2

intersection_count = float(len(intersection))

union = cluster1 | cluster2

union_count = float(len(union))

return intersection_count / union_count

cluster_ids = dict()

isplit_clusters = [

{

'cluster #1': set(1, 5, 14, 45),

'cluster #2': set(2, 3, 4, 6, 9),

'cluster #3': set(5, 7, 8, 10, 11),

'cluster #4': set(12, 13, 15, 17),

...

},

{

'cluster #45': set(1, 5, 14, 2),

'cluster #46': set(2, 4, 7, 8),

'cluster #47': set(3, 6, 11, 13),

'cluster #48': set(9, 12, 13, 15, 17),

...

},

...

]

integrity_threshold = 0.5

for index, split_cluster_data in enumerate(split_clusters[1:]):

previous_split_cluster_data = split_clusters[index - 1]

for cluster_id in split_cluster_data:

cluster = split_cluster_data[cluster_id]

for other_cluster_id in previous_split_cluster_data:

other_cluster = previous_split_cluster_data[other_cluster_id]

similarity = jaccard(cluster, other_cluster)

if similarity >= integrity_threshold:

# remove cluster id from current split_cluster_data

split_cluster_data.pop(cluster_id, None)

# assign that cluster the id from the previous cluster

split_cluster_data[other_cluster_id] = cluster

# move onto the next cluster in the current split_cluster_data

break

print(split_clusters)The above code attempts to find a similar cluster from the previous split distance, and if one is found that exceeds the threshold, it assigns it the ID of that cluster from the previous split. If one is not found, the cluster keeps a unique ID that will be processed in the next iteration. As with the initial clustering step, this logic can be further expanded upon with additional rules to look at clusters from further back in the race, or to account for predefined packs based on affiliations, social networks, etc. These rules can be used to more aggressively identify clusters over time and membership changes and gain further information into the cluster/pack changes throughout a race.

Research/Development Opportunities🔗

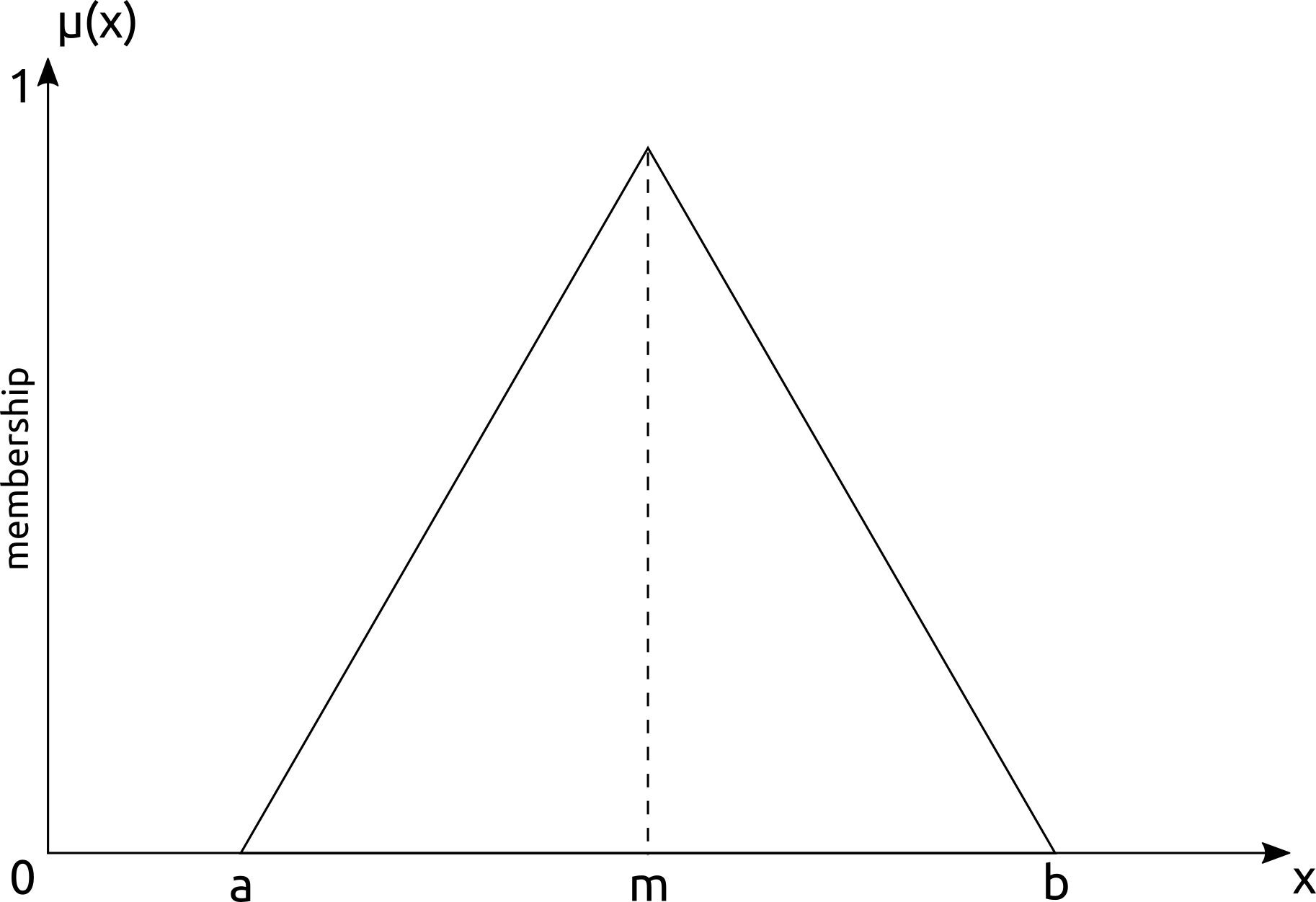

There is still more progress to be made in terms of integrating pack behavior into the current model of competition. The current approach for determining pack membership is a density-based clustering model which has a sharp cut-off, if a competitor is within a given distance of the rest of a pack, they are considered full members of that pack, if they are not, they have no membership of the pack. But even if a competitor barely exceeds that distance, being in the same proximity of the pack can potentially affect their/the pack’s behavior, and so I think that the models should be give nearby competitors a degree of pack membership. Models which allow for degrees of membership to clusters are called fuzzy clustering algorithms. In the context of a race, these methods allow for competitors to have partial membership to 0 or more packs. For example, a competitor who is trailing a pack may also be close to a pack behind them, so membership of each pack would be assigned to the competitor based on the distance from the competitor to each respective pack. Allowing for members to have partial membership in a pack/cluster lets us quantity the strength of membership for a competitor for a variable number of packs/clusters at a single point in time and yields more information about the behavior of competitors in a race.

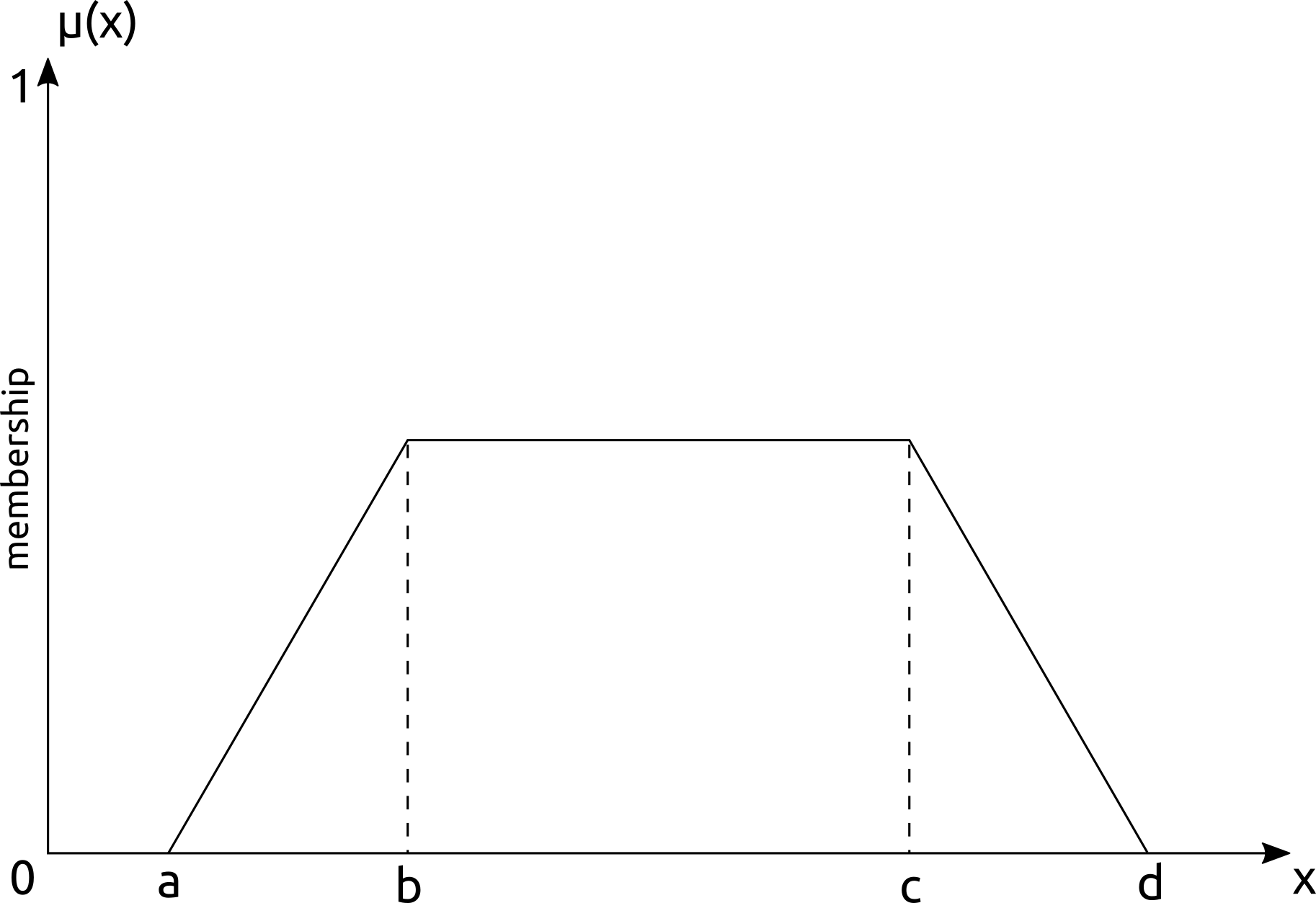

The key to determining the degree of membership of a competitor to a cluster/pack is through a membership function that reflects our intuition of membership to a function. If we consider the competitors in the interior of a cluster/pack to have a higher membership than those near the edge of a cluster/pack, our function will tend to be triangular, trapezoidal, or Gaussian. Or, if we consider membership to be based on the density of competitors around the athlete, the membership function will be shaped by the data itself. I would recommend using the density-based approach to determining membership using Fuzzy extensions of the DBSCAN clustering algorithm. If the fuzzy cluster/pack memberships need to be converted into crisp logic, we can use defuzzification

Here is a re-implementation of the DBPack algorithm that does this fuzzy clustering based on the density of the pack around competitors.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

class FuzzyBorderDBPack(object):

"""

An implementation of DBPack for fuzzy membership to clusters are the front and

and back of packs. Runners in the middle of the pack will have complete membership of the

pack. This implementation assumes a trapezoidal membership function, meaning that pack membership decreases linearly.

"""

OUTLIER = -1

def __init__(self, min_epsilon, max_epsilon, min_points):

self.min_epsilon = min_epsilon

self.max_epsilon = max_epsilon

self.min_points = min_points

def __call__(self, X, cluster_assignments):

pass

def membership(self, distance):

if distance <= self.min_epsilon:

return 1.0

elif distance > self.max_epsilon:

return 0.0

min_max_difference = self.max_epsilon - self.min_epsilon

neighbor_difference = self.max_epsilon - distance

return neighbor_difference / min_max_difference

def _neighbors(self, max_index, X, eps):

sample_count = len(X)

output = set([max_index])

current_point = X[max_index]

for i in range(max_index - 1, 0, -1):

neighbor = X[i]

distance = abs(neighbor - current_point)

if distance > eps:

break

output.add(i)

for i in range(max_index, sample_count):

neighbor = X[i]

distance = abs(neighbor - current_point)

if distance > eps:

break

output.add(i)

return output

def _expand_cluster(self, X, max_index, neighbors, clusters, cluster):

sample_count = len(X)

clusters[max_index][cluster] = 1.0

for i in range(max_index + 1, sample_count):

if i not in neighbors:

break

n_neighbors = self._neighbors(i, X, self.min_epsilon)

if len(n_neighbors) < self.min_points:

break

neighbors = n_neighbors

clusters[i][cluster] = 1.0

max_index = i

return max_index

def _expand_border_backward(self, X, core_index, clusters, cluster):

core_point = X[core_index]

for i in range(core_index - 1, -1, -1):

distance = abs(X[i] - core_point)

if distance >= self.max_epsilon:

break

clusters[i][cluster] = self.membership(distance)

def _expand_border_forward(self, X, last_core_index, clusters, cluster):

sample_count = len(X)

core_point = X[last_core_index]

for i in range(last_core_index + 1, sample_count):

distance = abs(X[i] - core_point)

if distance >= self.max_epsilon:

break

clusters[i][cluster] = self.membership(distance)

def fit_predict(self, X, y=None):

cluster = 0

max_index = 0

sample_count = len(X)

clusters = [dict() for _ in range(sample_count)]

while max_index < sample_count:

neighbors = self._neighbors(max_index, X, self.min_epsilon)

if len(neighbors) >= min_points:

self._expand_border_backward(X, max_index, clusters, cluster)

max_index = self._expand_cluster(X, max_index, neighbors, clusters, cluster)

self._expand_border_forward(X, max_index, clusters, cluster)

cluster += 1

else:

clusters[max_index][self.OUTLIER] = 1.0

max_index += 1

return clusters

But if a competitor can have degrees of memberships to a pack, then shouldn’t competitors be able to have degrees of a role? Or, if they have membership in multiple packs/clusters, have degrees of a role in each? Or have degrees of multiple roles in each? One possible model would be to have the degree of the role correspond to the degree of membership to the pack. For example, if a person leading the pack has created a small gap between themselves and the rest of the pack, they are still a leader of the pack but they may not have as much influence over the pace of the pack as they did before, because the rest of the pack may not think they are reachable. But, that approach would only allow for competitors to have degrees of a single role in cases where they only have membership.

Another approach, which could allow for competitors to have multiple roles, would be to assign degrees of a role based on the relative distance towards having full membership of that role. For example, if two competitors are at the front of the back, then both should be assigned a partial degree of the “Leader” role of the back, with the competitor in front having a higher degree of the role, and the person slightly behind having a lower degree of the Leader role, and a partial role as a Core member of the pack. This also needs to be more fleshed out, as there are many scenarios that would need to be accounted for, such as

- What if a pack/cluster has fewer members than it does roles? Are the roles all assigned to the 2 members, or are some eliminated? If so, which roles are considered, and to what degrees?

- How does one calculate when each role can start to be partially applied to a competitor? Or when a role should no longer be applied to a competitor?

I’m sure there are many other issues to be considered, or better ways of approaching this.

Application of Analysis🔗

The end goal of all competition analytics is to explain the outcome of competitions, identify potential flaws/improvements for future competitions, and to tell the story of the competition itself. Identifying patterns in behavior could lead to explanations of past race outcomes and upgraded race strategies that maximize individual and/or pack efficiency. Competition outcomes are tied to pack behaviors, but no model yet exists for accurate attribution of race outcomes. The development of such an attribution model could lead to automated race analysis, which would identify beneficial/harmful behaviors/outcomes in competitions for athletes and coaches everywhere, regardless of level of expertise.

Pack analysis can be applied to most racing sports, such as running, swimming, cycling, cross-country skiing, speed-skating, rowing and boating/sailing. Giving coaches, athletes, and spectators perspective of the effects of pack behavior can rejuvenate innovation in strategic race analysis and behavior. By adding information regarding pack membership and behavior coaches, athletes, and enthusiasts can gain new information on how they are affected by pack behavior in competition and the effect that packs had on past competitions.